Ancient Egypt - Tombs, Mummies, and the Journey to Eternity

In the previous post, I gave a general introduction to the history of Egypt. In this post, I will focus on the “afterlife” beliefs, and traditions in Egypt.

In Ancient Egypt, life was only half of the story. Death was not the end—it was a passage to a whole new existence. Everything they did, from mummification to the grand tombs in the desert sands, was designed to prepare for an afterlife they believed would last forever. This belief shaped their culture and left us with some of the most fascinating burial rites in human history.

Unlike many other cultures, where tombs were constructed after death, Egyptians began building their tombs during their lifetime, driven by their deep belief in the afterlife. Pharaohs typically initiated construction of their tombs at the start of their reign, recognizing that these monumental projects required significant time and resources. Completing the tomb before their death was essential, as it was believed to secure their journey to the afterlife.

It is important to realize that this process was not exclusive to the Pharaohs, and all Egyptians who had the means, strived to prepare for their journey to the afterlife. Wealthier Egyptians often commissioned elaborate tombs adorned with inscriptions, paintings, and goods they believed would accompany them in the next world. These tombs served not only as a resting place but also as a reflection of their social status and devotion to the gods. The less affluent, while unable to afford grand structures, still made efforts to prepare simpler tombs or burial sites that aligned with their beliefs. This shared focus on the afterlife shaped Egyptian culture, architecture, and society, leaving a legacy of intricate tombs and burial practices that continue to fascinate the world today.

While these burial practices and beliefs in the afterlife remained central to Egyptian culture, they were not static. Over 3,000 years, Egyptian religion and funerary traditions evolved, with shifts in gods, beliefs, and rituals. Some customs, like the cult of sacred animals, emerged later, while others faded over time. Even mummification, often thought of as a perfected process, went through numerous trials and errors before reaching the stage described by Herodotus. Early attempts sometimes resulted in failures—including bodies decomposing or even exploding—before the process was refined. Understanding this evolution adds depth to our appreciation of Ancient Egypt’s ever-changing spiritual and cultural landscape.

Beliefs About the Afterlife

Ancient Egyptians held an unwavering belief in the continuation of life beyond death, imagining a perfect existence in the afterlife. They envisioned a paradise called the Field of Reeds, a place mirroring the beauty of the Nile’s fertile lands. This idealized realm promised eternal happiness, where individuals could reunite with loved ones and continue their earthly activities, free of hardship. However, access to this paradise depended on careful preparation, spiritual devotion, and adherence to moral principles during one’s life. To ensure they would not have to perform labor in the afterlife, many Egyptians were buried with ushabti, small clay figurines believed to serve as substitute workers, or “clay slaves,” ready to take on tasks on their behalf in the next world.

Concept of Ma’at and Judgment of Souls

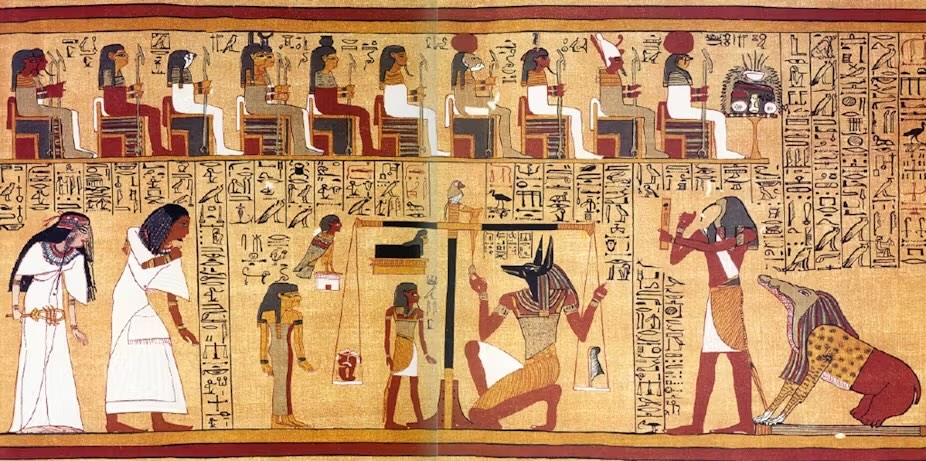

At the core of Egyptian spirituality was the concept of Ma’at, representing truth, balance, and cosmic order. Every person was expected to live in harmony with Ma’at, and this belief culminated in the “Weighing of the Heart” ceremony in the afterlife (pictured above). The deceased’s heart was weighed against the feather of Ma’at by the jackal-headed god Anubis. If the heart was light and pure, free of sin and dishonesty, the individual was deemed worthy of entering the afterlife. If not, their soul faced annihilation by a fearsome creature named Ammit, ending their journey for eternity. Ancient Egyptians believed that the heart is the seat of emotion, thought, and morality, and its purity was essential for a soul to enter the afterlife.

Journey to the Afterlife

The journey to the afterlife was believed to be perilous, requiring guidance and protection. Later Egyptians, around New Kingdom, relied on texts like the Book of the Dead (the photo above is a scene from this book), a collection of spells and instructions buried with the deceased to navigate the challenges of the underworld. Amulets, offerings, and intricate burial rituals were also essential to ensure safe passage. The ultimate goal was to reach Osiris, the god of the afterlife, and gain his blessing to enter the Field of Reeds, a reward for a life lived in accordance with Ma’at. These practices highlight the profound importance Egyptians placed on spiritual preparation and moral living.

Gods and Deities of Ancient Egypt

The journey to the afterlife in Ancient Egypt was guided by a pantheon of powerful gods, each with a unique role in protecting the deceased and ensuring their transition to eternal life. These gods were often depicted in tomb murals, temples, and other sacred art, serving as reminders of their significance in the afterlife and their constant presence in the lives of the Egyptians. Here are the most important deities associated in Ancient Egypt:

- Amon: Known as the “King of the Gods,” Amon was often associated with creation and hidden power. In later periods, he was linked with Ra as Amon-Ra, symbolizing his supreme role in maintaining cosmic order and renewal. While not exclusively tied to the afterlife, his presence represented divine authority and protection, reinforcing the spiritual foundation of the journey to eternity.

- Ra: The sun god and a central figure in Egyptian mythology, Ra symbolized the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. His nightly journey through the underworld represented renewal, ensuring the balance of the cosmos and the promise of a new day.

- Anubis: The jackal-headed god of mummification and protector of graves, Anubis ensured the preservation of the body and guided souls through the underworld. He played a vital role in the Weighing of the Heart ceremony, determining whether the deceased was worthy of eternal life.

- Osiris: As the god of the afterlife, resurrection, and fertility, Osiris ruled over the Field of Reeds, the Egyptian paradise. He judged the souls of the dead and embodied the promise of life after death, serving as a model for rebirth and eternal existence.

- Isis: The wife of Osiris and a powerful goddess of magic and protection, Isis was deeply connected to the rituals of death and resurrection. She used her magical abilities to resurrect Osiris and protect their son Horus, symbolizing the power of love and renewal.

- Horus: The falcon-headed god of kingship and protection, Horus was the son of Osiris and Isis. He played a role in avenging his father’s death and ensuring the continuation of divine order, often serving as a protector of the deceased in their journey to the afterlife.

- Thoth: The ibis-headed god of wisdom and writing, Thoth recorded the outcome of the Weighing of the Heart ceremony. His role as the divine scribe ensured justice and truth were upheld in the judgment of souls.

- Ma’at: The goddess of truth, balance, and cosmic order, Ma’at’s feather was used in the Weighing of the Heart ceremony to judge the purity of the deceased’s soul. She symbolized the ethical and moral principles that guided Egyptian life and the path to the afterlife.

- Ammit: The fearsome demoness, part lion, hippopotamus, and crocodile, was present during the Weighing of the Heart. If a soul was deemed unworthy, Ammit devoured the heart, condemning the individual to eternal oblivion.

- Hathor: The goddess of love, beauty, and joy, Hathor also played a role in welcoming the deceased into the afterlife, offering them comfort and ensuring a smooth transition into the next world.

These gods collectively represented the intricate beliefs surrounding death and the afterlife in Ancient Egypt. Their depictions in tombs, temples, and other sacred spaces served not only as a form of worship but also as a guide for the deceased on their journey to eternity.

The Magnificent Pyramids of Ancient Egypt

The pyramids of ancient Egypt stand as one of the most awe-inspiring achievements of human civilization. These colossal structures, built thousands of years ago, not only showcase the architectural genius of the ancient Egyptians but also serve as a window into their culture, beliefs, and society. Let’s explore the history, evolution, and significance of these iconic monuments.

A Burial Site for Kings

The pyramids were grand tombs built for Egyptian kings, particularly during the Old Kingdom period (circa 2686–2181 BCE). These monumental projects were often initiated by a king early in his reign to ensure its completion within his lifetime. Far from being mere burial sites, the pyramids symbolized the divine power of the king and his journey to the afterlife.

From Mastabas to Pyramids

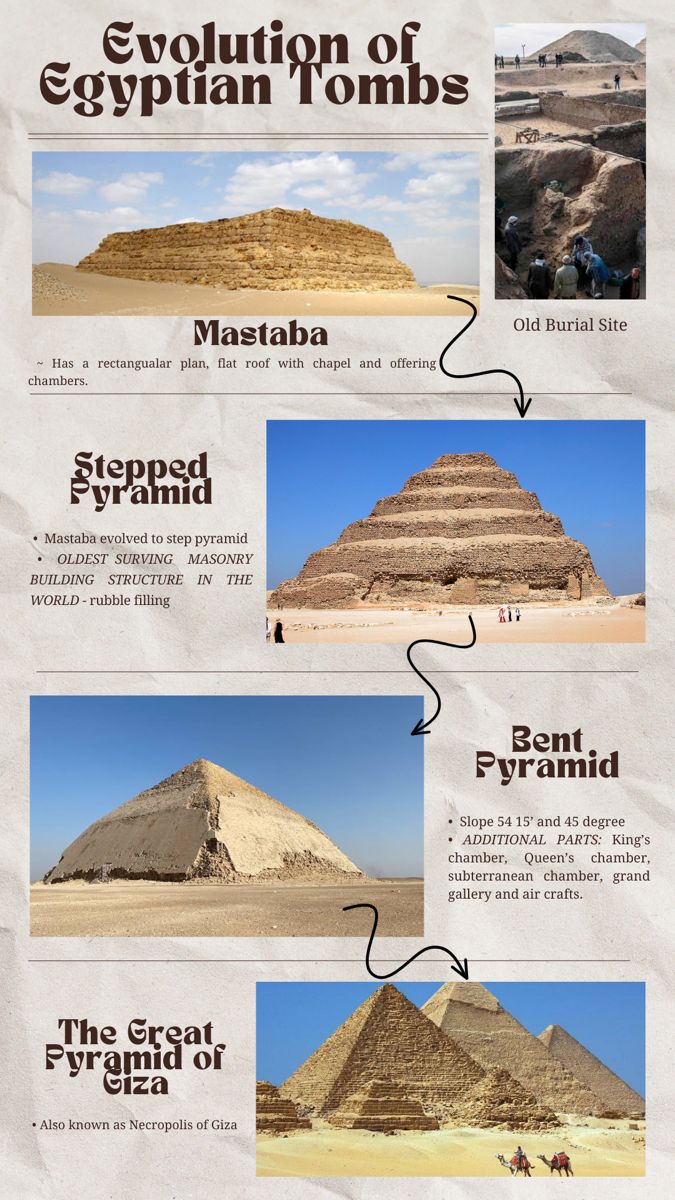

Before the pyramids, Egyptians used mastabas, rectangular, flat-roofed structures made of mudbrick or stone, as burial sites. These one-story tombs marked the early stages of Egyptian funerary architecture.

The true innovation came with King Djoser, who, along with his vizier and architect Imhotep, conceived the idea of stacking increasingly smaller mastabas on top of one another. This resulted in the Step Pyramid of Saqqara, Egypt’s first pyramid and a revolutionary leap in architecture. Saqqara, located on the west bank of the Nile, became the birthplace of pyramid construction.

The Transition to Smooth-Sided Pyramids

The design of pyramids evolved significantly during the reign of King Sneferu, Djoser’s successor. Sneferu embarked on a journey of trial and error, constructing three pyramids. His first attempt, the Meidum Pyramid, collapsed due to structural issues. His second, the Bent Pyramid, revealed an adjustment in slope mid-construction to prevent collapse. Finally, Sneferu succeeded with the Red Pyramid, Egypt’s first true smooth-sided pyramid, setting the standard for later pyramids.

The Pyramids of Giza: Peaks of Perfection

The Pyramids of Giza, built during the Fourth Dynasty, are the pinnacle of ancient Egyptian pyramid construction. The Great Pyramid, built for King Khufu, is the largest and most famous. Its original dazzling white limestone casing reflected sunlight, giving the pyramid a radiant appearance. Today, only remnants of this casing remain, most notably on the Pyramid of Khafre, where the top third still retains traces of its outer layer, though weathered.

Tragically, much of the limestone casing was removed during the Middle Ages due to earthquakes and repurposed for other construction projects.

A Herculean Effort to Build the Pyramids

The construction of these massive pyramids required immense resources and manpower. Contrary to popular belief, modern historians suggest that the pyramids were not built by slaves but by a workforce of skilled laborers. These workers, likely tens of thousands of them, were conscripted from across Egypt, and provided with food, housing, and medical care. The immense scale and speed of pyramid construction—spanning just four generations of kings—are a testament to the organizational capabilities of the Old Kingdom.

For example, the Great Pyramid of Khufu - the largest pyramid in Egypt - is estimated to contain over 2 million stone blocks, each weighing an average of 2.5 tons, with some granite blocks reaching up to 80 tons. Built over approximately 20–27 years, this means one block was placed every few minutes — a truly astonishing feat. At the time, the wheel had not been adopted in Egypt, so workers moved stones on sleds, lubricating the sand with water to reduce friction. Most of the limestone was quarried locally at Giza, while the granite came from Aswan, about 800 km away, transported via the Nile.

The exact methods used to lift and position the stones remain uncertain, but ramps are considered the most plausible solution, with theories ranging from straight to spiral designs. This incredible achievement, completed over 4,500 years ago, showcases the ingenuity and skill of ancient Egyptian builders. It’s no surprise that such a monumental task has inspired wild theories, but archaeological evidence points to remarkable engineering, resource management, and human labor as the true sources of this wonder.

The Pyramids as Symbols and Targets

While the pyramids were designed as eternal resting places, their grandeur ironically made them targets for tomb robbers. Even in antiquity, many pyramids were looted, undermining their purpose as secure burial sites. Instead, they became beacons announcing the presence of wealth, inviting the very fate they were meant to avoid.

Later Period Pyramids

While the pyramids of the Old Kingdom remain the most famous, pyramid construction continued in later periods, albeit on a smaller scale. During the Middle Kingdom and the Nubian period, smaller and less durable pyramids were built. These later pyramids, constructed with mudbrick rather than stone, have not withstood the test of time as well as their earlier counterparts. The architectural focus shifted from monumental pyramids to hidden rock-cut tombs, like those found in the Valley of the Kings during the New Kingdom. This change reflected both the practical challenges of protecting tombs from robbers and the evolution of Egyptian burial practices.

Other Pyramid Builders in the World

Egypt’s pyramids are undoubtedly the most iconic, but they are not the only ones in history. Civilizations around the world, such as the Mayans, Aztecs, and even the ancient Chinese, constructed pyramid-like structures, each with unique purposes and designs. The pyramids of Mesoamerica, such as the Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacan and the Pyramid of Kukulcán in Chichén Itzá, served as temples for religious ceremonies and sacrifices rather than tombs. In Sudan, the Nubian kingdom of Kush built over 200 smaller pyramids at Meroë, showcasing their cultural connection to ancient Egypt. These global pyramids demonstrate the universality of monumental architecture and its importance in expressing power, spirituality, and cultural identity. Moreover, the pyramid shape was likely the most practical way to build tall structures using only stone in ancient times, as it naturally distributes weight and ensures stability.

Mystical Theories and Myths

The grandeur and mystery of the Egyptian pyramids have inspired countless mystical theories and myths. Some speculate that the pyramids were constructed with the aid of extraterrestrials, citing their precise alignment with celestial bodies and the complexity of their construction as evidence. Others believe the pyramids have special energy fields or serve as conduits for cosmic power. While these theories are captivating, they often overshadow the remarkable ingenuity of the ancient Egyptians, who achieved these feats with simple tools, advanced planning, and human perseverance. The pyramids also play a prominent role in modern popular culture, featuring in stories of curses, secret chambers, and hidden treasures. While these myths add to the intrigue of the pyramids, they pale in comparison to the true story of their creation—a testament to human ambition and ingenuity.

Mummification, and Preserving the Dead

Mummification likely began long before recorded history, arising from the observation that bodies buried in shallow graves in the arid desert were naturally preserved. The hot, dry sands effectively desiccated the bodies, preventing decay. Early on, this natural preservation may have been associated with spiritual beliefs about the afterlife, as these intact remains gave the appearance of enduring beyond death. The first kings of Egypt were interred in simple graves with minimal preparation, relying on the desert’s environment for preservation. Over time, as Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife evolved, this natural process inspired the development of more deliberate and elaborate mummification techniques to ensure the deceased’s body was preserved for eternity.

The Mummification Process

The mummification process was intricate and took about 70 days to complete, divided into several key stages. First, the body was washed with water from the Nile, symbolizing purification. The internal organs, excluding the heart, were removed to prevent decay. Each organ was carefully embalmed and stored in canopic jars, with each jar guarded by one of the Four Sons of Horus, representing protection in the afterlife. The brain was extracted through the nose using specialized tools, as it was considered unnecessary for the afterlife.

The body cavity was then cleaned and packed with natron, a naturally occurring salt, to dehydrate the tissues and prevent decomposition. After 40 days, the body was unwrapped, and the natron was removed. The body was then anointed with oils and resins to restore flexibility and prevent further decay. Finally, the deceased was wrapped in layers of fine linen, often with protective amulets placed between the layers to safeguard the soul during its journey. Priests recited spells from the Book of the Dead during the wrapping process to ensure spiritual protection.

Rituals and Symbolism

Mummification was not just a technical process; it was a deeply symbolic and spiritual act. The rituals performed during mummification were designed to prepare the deceased for the afterlife and align their journey with the will of the gods. The “Opening of the Mouth” ceremony was one of the most important rituals, conducted by priests to restore the deceased’s senses and allow them to eat, drink, and speak in the afterlife.

The wrapping of the body was a sacred act, as each layer of linen symbolized the deceased’s protection and readiness for rebirth. Amulets such as the scarab, symbolizing transformation and renewal, and the Eye of Horus, representing healing and protection, were placed strategically within the wrappings. The face of the mummy was often covered with a mask, crafted from cartonnage (layers of linen and plaster) or precious metals, to preserve the deceased’s identity and connect them to the divine.

Social and Economic Aspects

Mummification was an expensive process, accessible primarily to the wealthy, including royalty and high-ranking officials. Elaborate mummification and burial practices were a mark of social status, with the Pharaohs receiving the most intricate preparations and being buried in grand tombs filled with treasures, food, and other necessities for the afterlife. Skilled embalmers worked in workshops, often near the Nile, where they combined practical expertise with religious duties.

For the less affluent, simpler methods were employed. These included natural preservation in desert sands, basic wrapping in linen, or communal burials. While these methods lacked the grandeur of elite mummifications, the underlying belief in the afterlife and the need to preserve the body remained universal. Even modest burials included grave goods such as pottery, tools, or small amulets to assist the deceased in their journey.

Interesting facts about Afterlife in Ancient Egypt

- Tutankhamun: A Pharaoh of the New Kingdom era, he is one of the most famous today, despite his minimal historical significance. His fame stems from the discovery of his intact tomb in 1922 by Howard Carter, the only Pharaoh’s tomb found untouched by looters, providing an extraordinary glimpse into Ancient Egyptian burial practices and treasures. Tutankhamun died young, and his tomb was prepared hastily, raising the intriguing question of how much more magnificent the tombs of other more powerful Pharaohs might have been.

- Mummifying Animals: The ancient Egyptians not only mummified humans but also animals, believing they played crucial roles in the afterlife. Sacred animals, like cats associated with the goddess Bastet or falcons linked to Horus, were mummified to honor the gods. Additionally, some animals, such as bulls, crocodiles, and ibis birds, were seen as sacred manifestations of specific gods and were embalmed accordingly. Others were mummified as offerings to the gods or to accompany their owners in the afterlife as pets or protectors.

- Staggering Number of Mummies: Over the course of Egypt’s long history, it’s estimated that more than many millions of mummies were created, including humans and animals. Mummification was practiced for thousands of years, from the early dynastic period to the Greco-Roman era, showcasing how deeply embedded the practice was in Egyptian culture.

- The Mummy Trade: There were so many mummies found in Egypt that they became a commodity. In the 19th century, mummies were sold cheaply in bazaars, sometimes even used as fuel for steam trains. During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, they were exported to Europe, where they were ground into powder for medicine, displayed in collections, or used in bizarre experiments.

- Tomb Curses: Many Egyptian tombs contained inscriptions warning against disturbing the burial site, invoking divine wrath upon intruders. While these “curses” were likely intended to deter grave robbers, they contributed to the modern myth of the “Curse of the Pharaohs,” especially after the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922.

- Books of the Dead: Wealthy Egyptians often included a personalized “Book of the Dead” in their tombs. These texts were filled with spells, prayers, and instructions to help the deceased navigate the underworld and gain access to the afterlife. The content varied depending on the individual’s needs, showing how customized and personal these beliefs were.

- Organs and the Afterlife: Most internal organs were removed and placed in canopic jars, but the heart was often left inside the body, as it was believed to be the seat of intelligence and emotion. In some periods, however, it was taken out and replaced with a heart scarab amulet to ensure a favorable judgment in the afterlife when weighed by Anubis. The brain, on the other hand, was considered unimportant and extracted in a rather gruesome manner—best left undescribed!

- Worker’s Tombs at Giza: The workers who built the pyramids were buried in a nearby cemetery. These tombs reveal that laborers were not slaves but skilled workers who were respected and provided with proper burials.

- Burial in Proximity to Sacred Sites: Ordinary Egyptians often sought burial near temples or sacred areas to gain proximity to the gods. Even in modest burials, the location was considered crucial for ensuring a successful journey to the afterlife.

- Tomb Robbing: We might imagine tomb robbing to be a relatively modern phenomenon, spurred by the discoveries of Egyptian tombs by archaeologists and Egyptologists. However, tomb robbing was a major issue even in ancient times, fueled by the immense wealth buried with pharaohs and nobles. Intriguingly, some of the most notorious tomb robberies were inside jobs, carried out by workers who had been involved in the construction or maintenance of the tombs. These individuals used their insider knowledge to bypass traps, navigate secret passages, and access hidden chambers, making them especially adept at looting the treasures meant to accompany the deceased into the afterlife

- State-Sanctioned Looting: During periods of political instability, there is evidence that officials themselves participated in or sanctioned the looting of tombs, redistributing wealth to fund state activities or pay workers.

- Rechless Excavations: Early Egyptologists often used destructive methods to unearth ancient treasures, prioritizing speed and spectacle over preservation. Tombs and temples were frequently blasted open with explosives or pried apart with brute force, damaging delicate structures and erasing valuable historical context. Painted walls were chiseled away, artifacts were ripped from their original settings, and mummies were destroyed as explained above. These careless practices permanently destroyed knowledge that modern archaeology could have uncovered.

This concludes my exploration of Ancient Egypt’s history. Naturally, Egypt boasts another 2,000 years of fascinating history beyond what I’ve covered here. While I’m not as familiar with this later period yet, I might dive into it in future travel blog posts. Our trip to Egypt is just around the corner, and we couldn’t be more excited!

FAQ

What’s inside the pyramids?

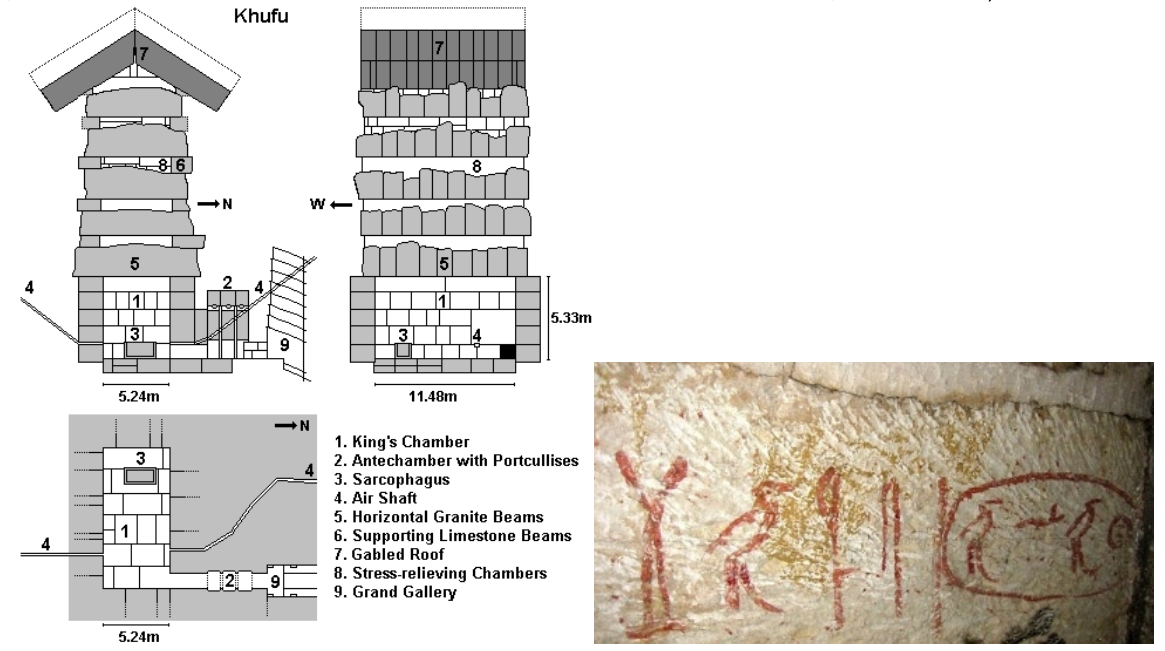

The interiors of the Pyramids of Giza are almost entirely constructed of stone, with only a few relatively simple and functional corridors and chambers. These spaces were primarily designed to safeguard the pharaoh’s remains and facilitate their journey to the afterlife. The Great Pyramid of Khufu is the most intricate, containing a series of chambers and passageways, such as the King’s Chamber, which houses a granite sarcophagus, the Queen’s Chamber, whose purpose remains unclear, and the subterranean chamber carved into the bedrock. It also features the Grand Gallery, a steeply inclined corridor leading to the upper chambers, and narrow air shafts that may have served symbolic or practical purposes.

Despite their purpose as tombs, no mummies or treasures remain inside the pyramids today. They were looted in antiquity, with valuables and burial goods stolen long before modern archaeologists arrived. The pyramids now appear bare, and their interiors primarily showcase architectural ingenuity rather than artifacts or decorations. These losses, however, do not diminish their historical and cultural significance as symbols of ancient Egypt’s power and belief in the afterlife.

Why did they stop building pyramids?

The ancient Egyptians stopped building pyramids due to the high costs, resource demands, and difficulty in mobilizing labor for such large projects. Pyramids also became easy targets for looters, prompting a shift to hidden, rock-cut tombs like those in the Valley of the Kings in Luxor, which offered better protection. Additionally, evolving religious practices and political changes reduced the emphasis on pyramids as symbols of power, with temples and mortuary complexes becoming the preferred way to honor the pharaohs and their connection to the divine.

What did Ancient Egyptians in later periods think about the Pyramids of Giza?

By the New Kingdom, the Pyramids of Giza were viewed as symbols of a distant, glorious past, associated with divine power and the achievements of the Old Kingdom. They were revered as sacred sites where kings united with the gods, and offerings were still made nearby. Pharaohs invoked the Pyramids to legitimize their rule, reflecting their ongoing spiritual significance. However, by the Late Period, they were also seen as practical sources of building materials, with some casing stones repurposed for other projects, showing a blend of reverence and utilitarianism.

But the pyramids must have surely be made by aliens, right? How could have humans built the pyramids 5000 years ago, when we can’t even built them today?

Some people speculate that the pyramids were built by aliens (or other fantastical theories), but extensive archaeological evidence strongly supports that they were constructed by humans during Egypt’s Old Kingdom period, around 2500 BCE. Here’s why:

- Archaeological Progression: The evolution of pyramid construction is well-documented. It began with simpler structures like the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, a series of stacked mastabas that formed the first large-scale stone monument. Later, the Bent Pyramid at Dahshur reflects an experimental transition toward smooth-sided pyramids. These examples show trial and error, consistent with human learning and engineering, not the work of aliens with advanced technologies.

- Construction Techniques: The methods and tools used to build the pyramids—such as copper chisels, wooden sledges, and ramps—were primitive but effective. Massive limestone and granite blocks were quarried, transported on sledges over sand, and arranged with remarkable precision. This process required skilled labor and careful planning, rather than mysterious or advanced technologies.

- Modern Feasibility: The claim that “we can’t build pyramids today” is misleading. Modern engineers could recreate the pyramids, but the effort, cost, and purpose make such a project senseless. The pyramids were monumental tombs built to reflect the centralized power and religious beliefs of ancient Egypt. Today, constructing such structures purely for vanity or burial would be unjustifiable.

- Archaeological Evidence of Workforce: Excavations near the Great Pyramid of Giza uncovered a worker’s village, complete with housing, bakeries, breweries, and tools. These findings reveal that a large, organized labor force — fed and housed on-site — undertook the construction. This logistical effort, supported by a centralized government, was massive but achievable by human means.

- Clear Evolution of Techniques: Quarry marks found on pyramid stones, abandoned or unfinished pyramids, and evidence of transportation paths provide additional proof of human involvement. These details reveal the practical methods used by ancient Egyptians, with no signs of extraterrestrial assistance.

- Ancient Writings Inside the Pyramid: The ceiling of Khufu’s King’s Chamber is composed of five massive stone layers stacked on top of each other, with empty spaces in between. Once the pyramid was completed, these spaces became inaccessible. However, an inept archaeologist used dynamite to investigate what lay above the ceiling, and created a small passage. In one of these gaps—whether the topmost or a lower one—hieroglyphs were discovered, reading “the friends of Khufu,” the name of a workers’ team (image below). If aliens had built the pyramid, how would this inscription have appeared?

While the scale of the pyramids is indeed awe-inspiring, the evidence overwhelmingly shows that humans built them through ingenuity, hard work, and organized labor. The idea of alien intervention is unnecessary and unsupported by facts.