Ancient Egypt - The Nile and the Land of Pharaohs

Before traveling to a new country, I usually research its geography and history to better understand the context of the place I’m visiting. This helps me write a few paragraphs about its history in my blog posts. However, as I’ve been learning about Ancient Egypt, it’s clear that its rich and complex history can’t be condensed into just a few paragraphs.

To do justice to this fascinating topic, I’m dedicating two blog posts to the history of Ancient Egypt, even before my trip. Covering its vast timeline, which spans thousands of years, is a monumental task requiring significant time and effort. In this post, I’ll focus on Egypt’s geography and the overarching history of Ancient Egypt. In the next post, I’ll dive into its afterlife beliefs, pyramids, and tombs.

The content for these posts comes from documentaries I’ve watched, books I’ve read, and, of course, insights from ChatGPT. A friend of mine who is an Egyptologist also reviewed the content, and gave me feedback, which I have reflected in the text.

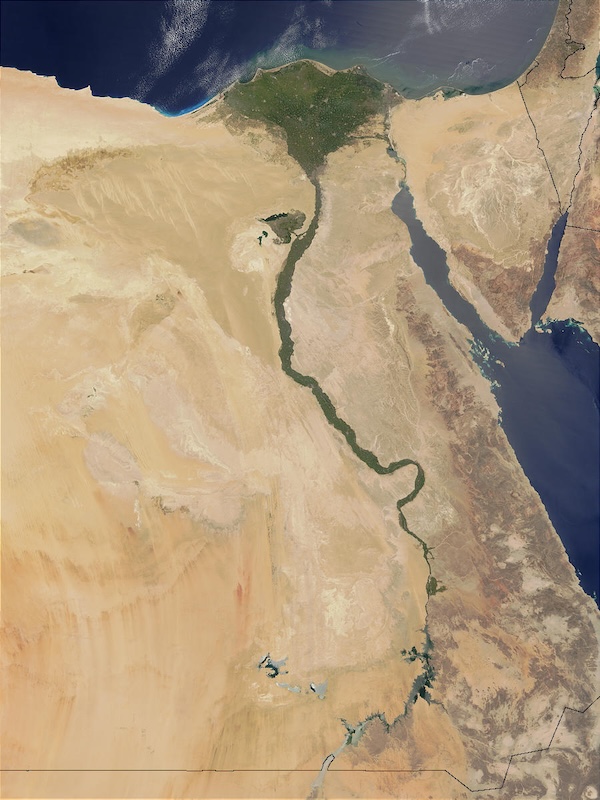

Nile River: Egypt’s Lifeline

As far back as around 2500 years ago, Herodotus called Egypt, the “gift of the Nile,” because Egypt owes much of its existence to this legendary river (not discounting the hard work and ingenuity of Ancient Egyptians themselves, of course). The Nile, widely considered the longest river in the world, shaped ancient Egyptian civilization. Even today, 95% of Egypt’s population live along the Nile River and its delta, despite comprising only 4% of Egypt’s total land mass. This striking imbalance underscores the Nile’s unparalleled significance for the past, present, and future of Egypt. However, this reliance on the Nile also has left the Egyptians vulnerable to the whims of nature, from ancient to modern times.

In the ancient times, Nile River’s predictable annual flooding replenished the soil, ensuring bountiful harvests in an otherwise arid environment (this is not the case anymore, since the construction of the Aswan Dam in 1960). This cycle of renewal allowed the Egyptians to develop advanced agricultural techniques, sustain their population, and construct monumental architectural feats like the pyramids.

The Nile’s utility went far beyond agriculture. It served as a natural highway, seamlessly connecting the vast expanse of the kingdom. Traveling downstream was as effortless as following the current, while the north-to-south prevailing winds enabled smooth sailing upstream. This unique dual functionality turned the Nile into a thriving trade route and a vital communication network, unifying Egypt and fostering its economic and cultural prosperity. Today, we understand the critical role of infrastructure, such as transportation and communication systems, in a nation’s success. No other early civilization was as fortunate to be centered around a lifeline like the Nile, a factor that likely gave Egypt its remarkable head start in history.

History of Ancient Egyptian Kingdoms

Many empires would consider themselves lucky to last through the reins of 31 kings but ancient Egypt would see the reign of 31 “dynasties of kings”, lasting for more than 3000 years. Ancient Egypt history is typically split into three sets of dynasties: Old, Middle and New Kingdoms, and the late period, spanning from around 3000 BC to 30 BC, when Romans annexed Egypt. There were a few tumultuous “intermediate periods” that were rife with instabilities, which I will not cover here.

The Old Kingdom (circa 2686–2181 BCE), often referred to as the Age of Pyramids, saw the construction of monumental architecture that continues to captivate the world. Pharaohs such as Djoser and Khufu oversaw the building of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara and the Great Pyramid of Giza, respectively, with these structures symbolizing the divine authority of the pharaohs and their role as intermediaries between gods and people. This period was marked by significant advancements in administration, with the establishment of a complex bureaucratic system to manage resources, labor, and trade. Art and sculpture flourished, with a distinctive style emphasizing idealized and formalized representations of royalty and nobility. However, the immense cost of pyramid construction and prolonged droughts contributed to economic strain, weakening centralized power and ultimately leading to the political fragmentation of the First Intermediate Period.

The Middle Kingdom (circa 2055–1650 BCE) is characterized as a period of reunification and cultural renaissance following the political chaos of the First Intermediate Period. Pharaoh Mentuhotep II re-established centralized rule from Thebes, restoring stability and initiating ambitious state-led projects. The Middle Kingdom witnessed a flourishing of literature, with works like The Tale of Sinuhe and The Instructions of Amenemhat reflecting philosophical and moral themes that resonated with a broader segment of society. Art became more naturalistic, depicting human figures with greater individuality and emotional depth. Large-scale irrigation projects expanded agricultural productivity, helping to sustain the growing population. However, the Middle Kingdom left fewer monumental structures than its predecessors, and despite its achievements, it gradually declined due to internal struggles and increasing pressure from foreign groups, setting the stage for the Second Intermediate Period and the rise of the Hyksos.

The New Kingdom (circa 1550–1070 BCE) marked the height of Egypt’s power and territorial expansion, often referred to as the Empire Age. Pharaohs like Hatshepsut, Akhenaten, and Ramses II transformed Egypt into a dominant force, securing wealth through trade, diplomacy, and military conquests that extended Egyptian influence into Nubia, the Levant, and beyond. Lavish temples such as those at Karnak and Luxor reflected the wealth and religious devotion of the ruling elite, while tombs in the Valley of the Kings showcased advancements in funerary practices. Akhenaten’s radical shift toward monotheism, worshiping Aten as the sole deity, briefly disrupted traditional religious structures but was reversed after his death. The New Kingdom also saw increasing conflicts with powerful empires like the Hittites, culminating in events such as the famous Battle of Kadesh. By the late New Kingdom, economic troubles, priestly power struggles, and external invasions contributed to the empire’s decline, leading to the Third Intermediate Period.

The Late Period (circa 664–30 BCE) began with the 26th Dynasty, when Egypt briefly regained independence under native rulers like Psamtik I, who revitalized the nation by fostering cultural and artistic traditions inspired by its glorious past. However, Egypt faced increasing challenges from foreign powers, including invasions by the Assyrians and later the Persians, who conquered Egypt in 525 BCE under Cambyses II, marking the beginning of the 27th Dynasty. Persian rule brought administrative and infrastructural changes, integrating Egypt into a vast empire while respecting its religious institutions. Despite occasional revolts and brief periods of independence, Egypt remained under Persian dominance until Alexander the Great’s conquest in 332 BCE, which ushered in the Ptolemaic dynasty—a fusion of Greek and Egyptian traditions. The Ptolemies ruled as pharaohs, blending Hellenistic influences with ancient customs, and Cleopatra VII, the last Ptolemaic ruler, became renowned for her intelligence and alliances with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. Her defeat and death in 30 BCE marked the end of Egyptian rule and Egypt’s transformation into a Roman province, symbolizing both the conclusion of its independence and the enduring legacy of its cultural and political significance.

Ancient Egypt: A Culture That Transformed Over Time

When visiting Egypt as a tourist, it’s easy to assume that Ancient Egyptian culture remained unchanged over time and to view everything through a single lens. However, Ancient Egypt’s history spans over 3,000 years, during which its customs, art, religious beliefs, and society evolved significantly. The Egypt of the Old Kingdom, when the first pyramids were built, was vastly different from the Egypt of the New Kingdom, when pharaohs ruled over a vast empire, and even more so from the Late Period, when foreign influences shaped the history, and culture.

Despite these transformations, some core elements remained constant throughout the millennia. The Nile continued to sustain Egyptian civilization, ensuring agricultural prosperity. The concept of Ma’at—order, balance, and justice—remained central to governance and daily life. The belief in an afterlife endured, reflected in elaborate burial practices and monumental tombs. Writing, particularly hieroglyphs, persisted as a vital tool for recording history, religious texts, and administrative affairs. Even as their world changed, the Egyptians maintained a deep connection to their past, honoring traditions that linked generations across centuries.

Important Cities and Their Heyday in Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt’s history is closely tied to its vibrant cities, each of which played a significant role during different eras. These cities were not only political and religious centers but also hubs of culture, learning, and trade.

Memphis: Capital of the Old Kingdom

Founded around 3100 BCE by the legendary Pharaoh Menes, Memphis was the capital of the Old Kingdom and a pivotal city in early Egyptian history. Situated strategically at the mouth of the Nile Delta, it became a center for administration and trade. Known for its grand architecture, including the nearby Pyramids of Giza, Memphis also housed the massive temple of Ptah, a testament to its role as a religious and cultural hub during its peak.

Thebes: Religious Center of the New Kingdom

Thebes rose to prominence during the New Kingdom (circa 1550–1070 BCE) as a religious and political powerhouse. Situated in Upper Egypt, it was home to the monumental temples of Karnak and Luxor, dedicated to the god Amun. The Valley of the Kings, located nearby, served as the burial site for pharaohs, including Tutankhamun and Ramses II. Thebes epitomized the grandeur of Egypt’s imperial zenith, symbolizing its wealth, piety, and artistic achievements.

Alexandria: A Hub of Learning and Trade in the Late Period

Established by Alexander the Great in 331 BCE, Alexandria became a beacon of intellectual and economic activity during the Ptolemaic period. Its legendary Great Library and Museum attracted scholars from across the ancient world, while its strategic location on the Mediterranean made it a vital center for trade. As the capital of the Ptolemaic dynasty, Alexandria blended Egyptian, Greek, and Roman cultures, leaving a lasting legacy that shaped the ancient and modern worlds.

These cities, each unique in their contributions, represent the diverse and dynamic history of Ancient Egypt.

Technological and Artistic Contributions of Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt’s enduring legacy is rooted in its remarkable technological and artistic achievements, which influenced countless civilizations and continue to captivate us today.

|

|---|

| Hieroglyphs vs. hieratic vs. demotic |

Innovations such as Hieroglyphics and Papyrus

The Egyptians developed a sophisticated system of writing, beginning with hieroglyphs, which were used for over three millennia. This intricate system combined pictorial symbols, ideograms, and phonetic elements to convey complex ideas. Over time, more streamlined scripts evolved for practical purposes: hieratic, a cursive form for religious and administrative use, and later demotic, a simplified script for everyday writing. These systems coexisted for centuries, showcasing the Egyptians’ adaptability in written communication. The invention of papyrus, a durable and lightweight writing material, complemented these scripts, enabling the creation of records, literature, and official documents that shaped the administrative and cultural fabric of ancient Egypt.

|

|---|

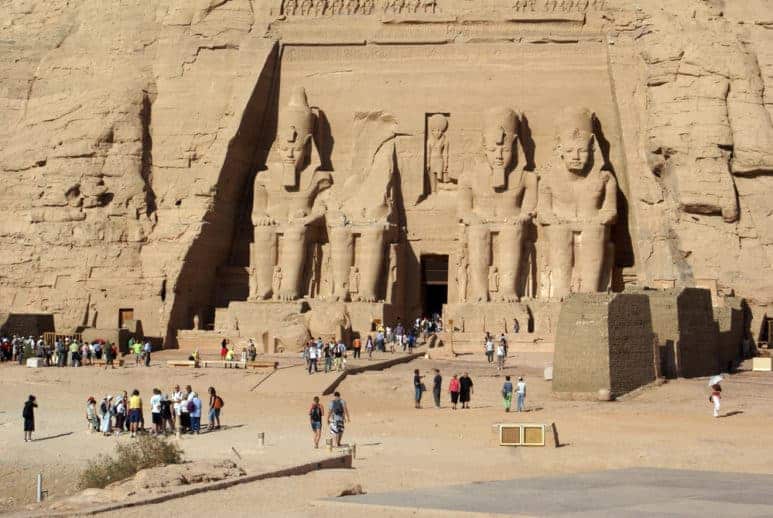

| Abu Simbel Temple in Southern Egypt |

Monumental Architecture: Temples and Statues

Egyptian architects and craftsmen mastered the art of monumental construction, leaving behind awe-inspiring structures such as the temples of Karnak and Abu Simbel. Colossal statues, like those of Ramses II, showcased not only their engineering prowess but also their devotion to the gods and the pharaohs. These enduring symbols of power and spirituality remain iconic representations of ancient Egypt’s grandeur.

|

|---|

| Nefertiti bust, believed to have been crafted in 1345 BC, now housed in Egyptian Museum of Berlin |

Artistic Styles and Their Evolution

Egyptian art was characterized by its formal, highly symbolic style, reflecting religious and societal ideals. Paintings often depicted people in idealized forms, appearing slender, tall, and youthful, regardless of their actual age or appearance. Figures were typically shown in profile, with heads, legs, and feet viewed from the side, while torsos faced forward, a convention designed to present the most recognizable aspects of the human body. From vibrant tomb paintings to intricate jewelry, Egyptian art captured the essence of their culture, blending functionality with profound aesthetic beauty.

Through these contributions, ancient Egypt demonstrated an unparalleled ability to merge practicality with creativity, leaving a lasting impact on human history.

Cultural and Social Structure of Ancient Egyptian Kingdoms

Ancient Egypt’s cultural and social structure was deeply intertwined with its religious beliefs and hierarchical society. Each level played a vital role in maintaining the stability and grandeur of the civilization.

Pharaohs and Their Divine Role

The pharaoh stood at the pinnacle of Egyptian society, serving as both a political ruler and a divine figure. Regarded as the earthly embodiment of Horus and, after death, associated with Osiris, the pharaoh was the primary intermediary between the gods and the people. Central to their rule was the maintenance of Ma’at—the concept of cosmic order, balance, and justice—which justified their authority and reinforced their absolute power. This divine status was reflected in the construction of grand temples and monuments dedicated to both themselves and the gods. In the Old Kingdom, this belief likely motivated the massive labor force that built the pyramids, designed as grand tombs to ensure the pharaoh’s journey to the afterlife.

Over time, however, the pharaoh’s divine authority waned. Economic difficulties, internal strife, and the increasing influence of powerful priests—particularly those of Amun—gradually diminished their control. By the later periods, oracles, often interpreted by high-ranking priests, played a role in state decisions, shifting power away from the throne. Additionally, the practice of tomb raiding, even by officials (more on that in the second post), undermined the inviolability of royal burials, further eroding the perception of pharaohs as untouchable divine beings.

Society: Nobles, Priests, and Workers

Below the pharaoh were the nobles and priests, who formed the upper echelons of society. Nobles governed provinces, collected taxes, and ensured the smooth functioning of the kingdom, while priests oversaw religious rituals and maintained the temples, acting as guardians of spiritual life. Workers, including farmers, artisans, and laborers, formed the backbone of Egyptian society. They built monumental structures, cultivated the land along the Nile, and created the goods that fueled the economy. Despite their different roles, all members of society contributed to the shared goal of sustaining Egypt’s prosperity and honoring the gods.

This structured social system, deeply rooted in religion and tradition, allowed Egypt to thrive for millennia.

Interesting facts about Ancient Egypt

- Pyramids are so old: Julius Caesar lived closer to our time than the Pyramids of Giza were to his. Let that sink in!

- Lower and Upper Egypt: Confusingly for us, Ancient Egyptians referred to the area below the Nile delta as Upper Egypt, and the delta region as Lower Egypt, because Nile flows south to North.

- East vs. West Bank of the Nile: Most cities in Ancient Egypt were built on the east bank of the Nile, as it symbolized life and rebirth due to the rising sun. In contrast, the west bank was reserved for burials, as the setting sun represented the realm of the dead.

- Adoration of cats: Egyptians love of cats likely began because cats helped protect food stores by hunting mice and rats, a critical role in their highly agricultural society. Cats were so revered that harming one, even accidentally, was considered a grave offense. Mummified cats, often associated with religious offerings to the goddess Bastet, became widespread, particularly during the Late Period.

- Hieroglyphs: The Egyptian writing system included over 700 symbols and was often used in tombs and temples to ensure the deceased’s safe passage to the afterlife.

- Pyramids: The Great Pyramid of Giza is the last of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still standing. It was originally covered in polished limestone, which reflected sunlight, making it shine like a “gem.” I will discuss pyramids in more detail in the next post.

- Papyrus: Ancient Egyptians were pioneers in creating paper-like material from the papyrus plant, which grew abundantly along the Nile. This innovation enabled the recording of history, trade, and religious texts.

- 365-Day Calendar: To manage their agricultural schedules and predict the annual flooding of the Nile, Egyptians developed a solar calendar with 365 days, which became the basis for the modern calendar.

- Medicine and Surgery: Egyptians practiced advanced medicine for their time, including setting broken bones, performing surgeries, and using natural remedies. They even documented medical knowledge in texts like the Ebers Papyrus.

- Wigs and Cosmetics: Both men and women in Ancient Egypt wore wigs and makeup. Eyeliner was not only decorative but also protected their eyes from the sun’s glare and infections.

- Beer Brewing: Beer was a staple in the Egyptian diet, consumed by all social classes. It was often made at home and even used as a form of salary.

In the next post, I will focus entirely on the Ancient Egyptians’ remarkable emphasis on the afterlife and how it has greatly contributed to our understanding of Ancient Egypt today.

FAQ

How were the Ancient Egyptians so prolific that museums worldwide, as well as those in Egypt, are filled with their artifacts, apart from all the impressive temples and tombs they left behind?

I can think of multiple reasons for that:

- The Ancient Egyptians were prolific due to their long-lasting civilization, which spanned over 3,000 years, and their emphasis on preserving their culture and beliefs. With advanced engineering and artistic skills, they constructed monumental structures like pyramids, temples, and tombs.

- Their religious devotion to the afterlife led to the creation of elaborate burial practices, resulting in countless artifacts designed to accompany the deceased.

- The arid desert conditions in Egypt, which played a significant role in preserving these artifacts and sites, protecting them from decay over millennia.

- They mostly used stones to build their pyramids and temples, and stone is more durable than wood or clay.

- Many of their temples were buried under the sand, and the tombs though were mostly robbed, they were under the ground, so many of their artifacts survived.

- Egyptians loved to write! They carved on stones, and wrote on papyrus, which was also unique to them.

- Perhaps seeing the masterpieces of their predecessors inspired them to strive for similar remembrance—though this is just a hypothesis.

How were the hieroglyphs decoded?

The discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799, now in the British Museum, was key to decoding Egyptian hieroglyphs. The stone featured the same text in Greek, Demotic, and hieroglyphs. French scholar Jean-François Champollion deciphered the hieroglyphs in the 1820s by comparing the Greek text with the hieroglyphs, identifying their phonetic values. His work showed that hieroglyphs combined phonetic sounds, ideograms, and determinatives, unlocking insights into ancient Egyptian culture and history.

Champollion’s knowledge of Coptic, a language descended from ancient Egyptian, was vital to his success. Spoken by Egypt’s Christian population, Coptic preserved elements of the ancient language. Using Coptic, Champollion identified the meanings of hieroglyphic symbols, bridging the ancient and modern worlds and advancing the understanding of Egyptian civilization.